Behind double-plated smudged glass, Todd Abramson sits in a wheeled office chair, the seat cushion flattened from overuse. Beside him is a stack of vinyl. He selected some days prior from his home collection and others moments ago from the radio station’s archives. The first record he chooses is “Hot Rails To Hell” by Blue Oyster Cult, a song with a sense of humor and perfect for the mid-80 degree summer day. It kicks off another week of WFMU’s Todd-O-Phonic Todd show.

The Jersey City radio station is the orphan of Upsala College. The school closed in 1995, but the station remained, shrewdly purchased by several staff members before the college officially went under and the license for 91.1 FM went on the auction block. WFMU is where people turn for the underground, alternative, avant-garde, and independent. And on Saturdays at 3:00 p.m., Abramson takes the helm, spinning decades-old, nearly-forgotten garage dittys alongside fresh-faced first singles from artists eager to become known.

At 55, Abramson is an undisputed tastemaker in his world. He’s been instrumental in sharing and promoting music for over 30 years. It started at Maxwell’s in Hoboken. For decades, Maxwell’s was New Jersey’s answer to the great, gritty clubs across the Hudson. In the back, behind the bar and restaurant, was a red, 200 person capacity room that offered a stage to underground acts of all degrees of notoriety. With Abramson’s ear and network of artists, agents, and record labels, Maxwell’s became a club with a lore approaching that of CBGBs. It hosted countless bands before they made it big — Mudhoney, Nirvana, The Yeah Yeah Yeahs, The Strokes — all of which didn’t fill half the venue at the time. It was beloved by both musicians and fans. The musicians loved Maxwell’s because they always got a meal and respect — a rarity, whether they were headlining a sold out show or opening to an audience of friends and parents. The fans loved Maxwell’s because it reeked of cool and because they were from New Jersey and because it was theirs.

However, as time passed, Hoboken gentrified, and Maxwell’s became the kid with facial piercings in a wealthy prep school. It’s audience no longer lived in Hoboken — largely priced out or driven away by the changing vibe, and the one square mile city no longer had enough street parking to accommodate its residents, let alone the bands with vans and the hundreds flocking to hear them play. Abramson, aware of the new demographics and conscientious about not overstaying his welcome, made the decision with his partners to close the club before it lost its mystique. In 2013, Maxwell’s threw a farewell party featuring the The Bongos, the first band to play the space, bookending a legendary run.

With a self-deprecating laugh, Abramson is quick to share credit for Maxwell’s success. Steve Fallon, the original owner, was essential to the club, as was an inclusive and welcoming staff, a stark departure from the aloof punk attitude often displayed elsewhere. This is a disposition reflected by Abramson himself. Despite his wealth of music knowledge, he approaches conversation about the subject with excitement and generosity. He wants to hear about what others are into and sometimes recommends songs with a disclaimer, “not everyone will like it.”

Music also led him to his wife. He met Cheryl at a show at Maxwell’s. They liked the same things and saw many of the same bands. They married in 1994, and music remains a keystone of their relationship. When he books a gig, she’s there with him, sometimes taking tickets or helping coordinate. Abramson speaks of his wife often and with pride. He introduces her as “the legend.” While he tends to hang back when seeing a show, she navigates to the front to dance. She is dynamic, talkative, and open. Every week, Abramson dedicates several songs to Sissophonic Cheryl, an on-air moniker he’s given her to match his own.

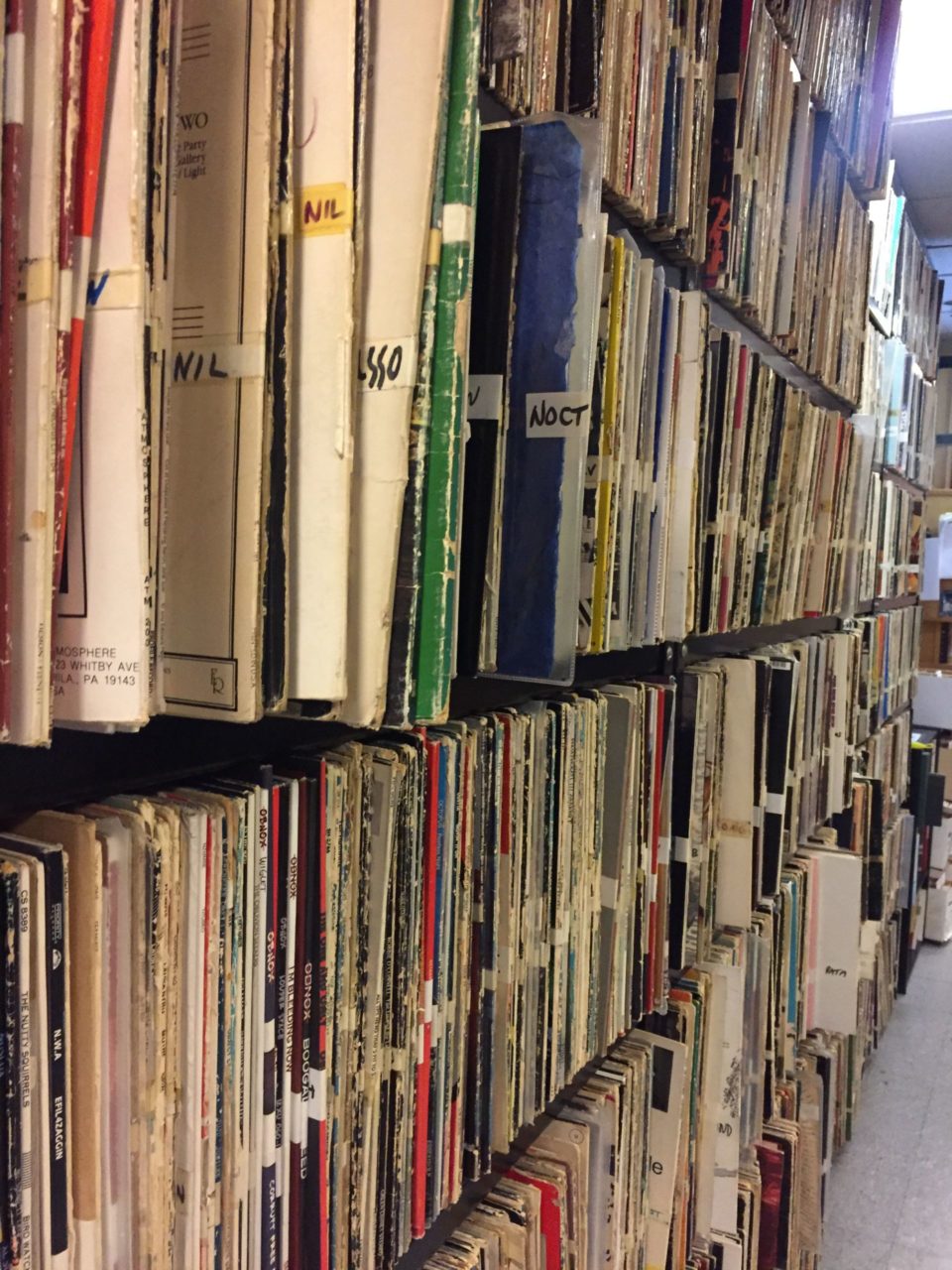

After exiting Maxwell’s with grace and goodwill, Abramson went from guest deejaying to a weekly radio slot Saturday afternoons on WFMU. From the outside, the station on Montgomery Street in Jersey City looks like an average, slightly worn residential building. Inside, the hallway is narrow, the walls lined with band posters, World War II propaganda, and signs like “Hippies use other door” and “Hugs: $1. Punch in the face: free.” This is where Abramson feels at home. The people there are passionate. The deejays are not paid. Everyone is driven by their enjoyment of music and the small sense of validation that comes from sharing what you love.

On the air, Abramson keeps it upbeat, believing it’s his mission to electrify listeners for Saturday night. He conveys an energy, partially through his celebratory cadence but also through the many facets of the show. When the microphone is off, it’s a frenetic blur of activity. There are doorbells to answer four flights downstairs, CDs to grab during songs, and records to cue up on two turntables. There’s also usually an interview to do or a band or two playing a live set, like Los Vigilantes from Puerto Rico did recently.

Then there’s Monty Hall. Abramson is back in the booking game, now for the space on WFMU’s first floor. Starting slowly, the venue has grown to feature a steady stream of notable acts, including, Pinegrove, Ducktails, and Waxahatchee — talent usually snapped up by Brooklyn clubs that have the advantage of a bar (Monty Hall lacks a liquor license) and the cool kid air that the borough connotes.

At first glance, it seems that many things have changed for Abramson in the last five years — a new club, a radio show, and more free time than he used to have. But often change is just new clothing on the same man. Abramson is still discovering, sharing, and promoting underground music, only now it’s on a different stage.

You must be logged in to post a comment.