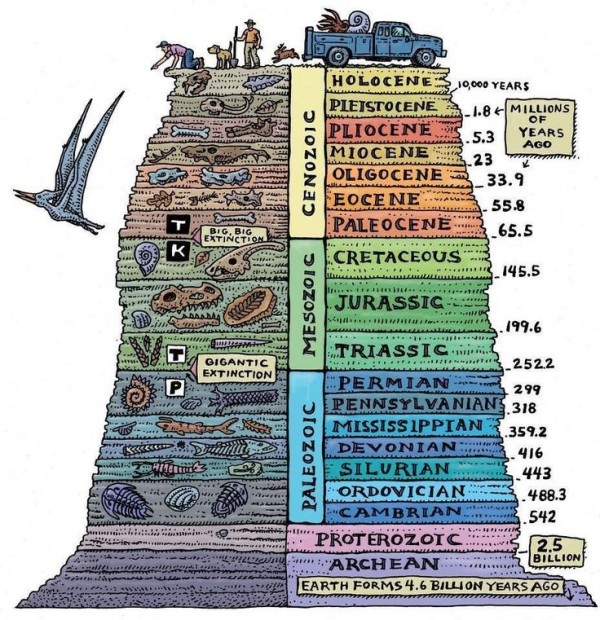

A few weeks ago, the Embankment Preservation Coalition organized a presentation about the geography of Jersey City at Grace Van Vorst church, headed by Luke Schray, an urban planner and board member of the coalition. When his home was flooded in Hurricane Sandy, his interest was piqued into the geography of Jersey City. But “to understand our current landscape, we have to go very far back in time,” Luke said.

I’m going to assume you know very little about this topic (like me) and start with the basics:

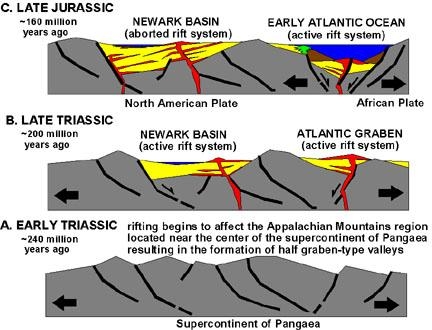

Somewhere around 300 million years ago, all the continents used to be squished together into one big supercontinent called Pangea:

(What eventually became) Africa was especially excited to give (what eventually became) North America a kiss during this period and all that kissing (i.e. huge landmasses crushing together in slow motion over millions of years) created our mountains and a dense carbon substance that we now call coal, which is rich in the United States and has fueled Jersey City’s beloved Powerhouse!

During the Triassic Period (let’s call this 200-250 million years ago), Pangea started to break apart.

This breakup created major rifts and pushed a bunch of magma (hot fluid or semi-fluid material below earth’s crust) up to the surface and helped to drive the continents apart. This event created the rift basins all over the place, including the Newark Basin.

The magma would eventually harden and, after millions of years, erode to expose what we know today as the Palisades Sill.

So the next time you’re driving through/hiking up the Palisades, imagine all those cliffs crashing together and breaking apart in slow motion and tell the person next to you that your view is spanning over 200 million years of geological time.

Not long, after all, this breaking apart started, earth tried to end the party (for the second time). The Permian Mass Extinction or ‘The Great Dying’ as it is affectionately nicknamed, killed off more than 95% of all living things. “We don’t quite know what happened but we think it was a rapid increase of Co2 levels in the atmosphere and that shocked all life and weather systems,” Luke said.

Left for us were the building blocks or rather building minerals, of Jersey City’s foundation.

Graphite, basically a high-grade coal, can be found all over The East Coast. This lead to the Joseph Dixon Crucible Company, maker of crucibles, crayons and graphite-based stove polishes and lubricants along with those famous Dixon Ticonderoga pencils, to set up shop in Jersey City (after moving from Salem, MA).

![]()

Serpentinite, which sort of looks like kryptonite but isn’t, lies underneath Manhattan and the Jersey City waterfront. It is comprised of bits of the ocean floor that were scooped up in the collision and compounded together.

Sandstone, a sedimentary rock consisting of sand or quartz grains jammed together, typically red, yellow, or brown in color is especially prevalent around Jersey City. Particularly good examples of this can be found on the embankment walls. Portions of the 6th street embankment feature reddish tint sandstone while blocks feature grayer, glumpy examples.

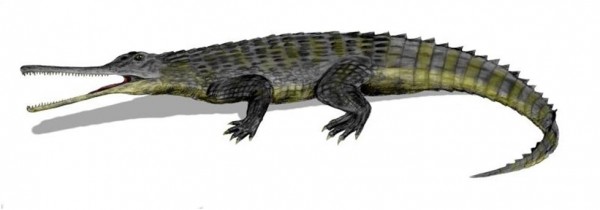

Because of its extremely porous nature, sandstone is really good at preserving fossils. This gives us clues into what kind of terrifying animals were roaming around New Jersey like… the Phytosaur, a carnivorous alligator-like creature that could grow up to 36 feet long.

And the Icarosaurus, a winged lizard that flew around the lush eastern seaboard and will now haunt your dreams. Both were discovered in North Bergen and you can visit their bones at the American Museum of Natural History.

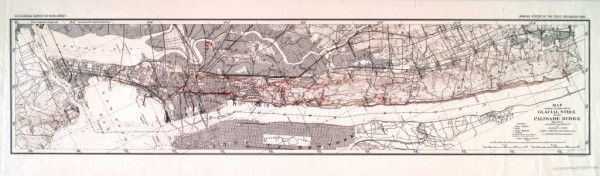

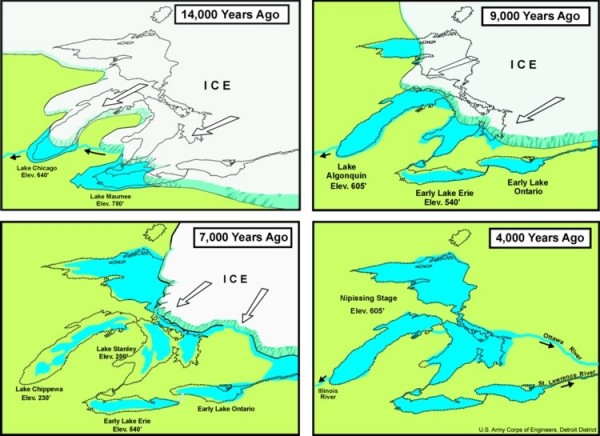

The Ice Ages (did you know there was more than one?) began about 2.4 million years ago and lasted until 11,500 years ago. During this time, the earth’s climate see-sawed between very cold periods where glaciers covered the world and very warm periods that made the glaciers melt. Theorizing that “every feature on a landscape was created by a force,” Luke illustrated that the Hudson River was carved by these glaciers and helped form the Jersey City, Hoboken, Staten Island and Brooklyn waterfronts.

We have proof of the glacier’s residence in Jersey by the striations or grooves, it left on rocks. Sand and grit would get caught up on the surface and the melting glaciers would drag it across.

When the glaciers melted the sea level rose 360 feet, Lake Erie swelled to three times its usual volume and the actual temperature of the earth went up seven degrees. Hudson valley was catastrophically flooded and the Verrazano narrows became completely washed out.

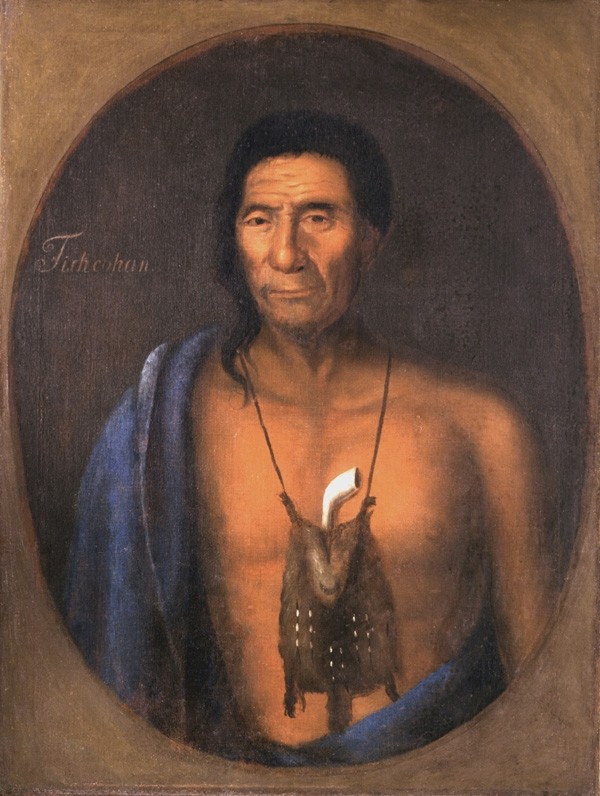

The first natives to Jersey City were the Lenni-Lanape, part of the Algonquin Indian tribe. Evidence suggests that their ancestors originated in Siberia and then crossed the Bering Strait into North America and slowly migrated around the eastern seaboard about 10,000 years ago. Mastodons and Mammoths were roaming New Jersey and the surrounding areas at this time.

The Lenni-Lenape tribes survived off the land for thousands of years but it didn’t take long for the Europeans to push them of the Delaware Valley out as colonization moved in.

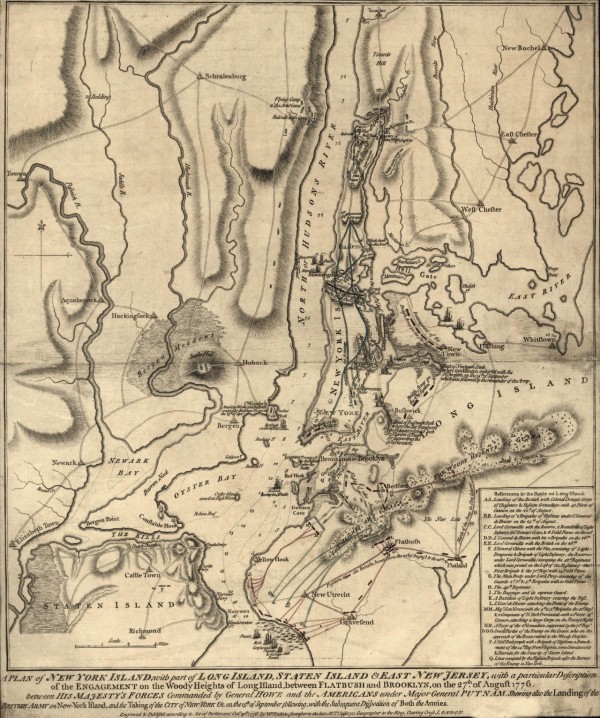

In 1524 explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano and the Dutch East India Company and set out to find a North West passage around North America to access Indonesia and take control of their spice market but instead landed in New Jersey and shifted their focus to bringing the abundant furs of the area back to Europe.

Henry Hudson who landed here in 1609, described the area as an “ecological paradise of furs and food.” Animals were abundant; deer, ground hogs, buffalos, panthers, bears, elk, foxes, wild cats, wolves, raccoons, beavers, otters roamed the region with no shortage of birds and fish.

By the early 1600s, the Dutch had uprooted many of the Lenni-Lenape communities, settled Jersey City and began to erect homesteads. One of the first Jersey City residents to build was Cornelius Van Vorst who in 1654 erected his house in Harsimus.

From this point on, the population of the area only grew and the Lenni-Lenape were pushed out.

However, many of the community names and trails that the Lenni-Lenape used still exist today.

In 1829, the local population was around 1,000 but by 1865, it had grown to 40,000 people.

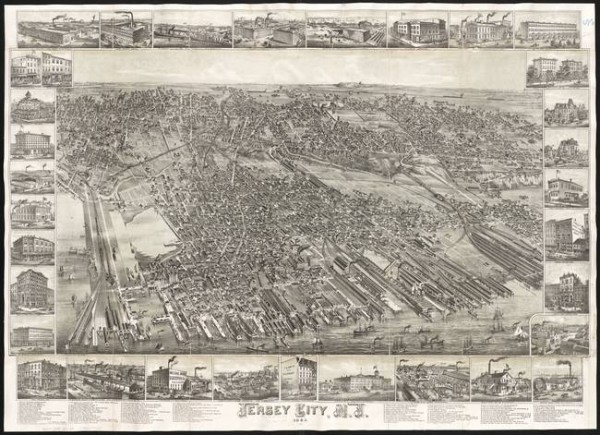

By the late 1880s, the robber barons, industrialists, and Ellis islanders had moved in. A complex network of railroads was installed and Jersey City grew very rapidly. This is when Jersey City and Manhattan’s waterfront began to change shape to accommodate travel and commerce. “Straight lines are almost always an indication that man has been at work,’ said Luke.

In 1927 the Holland Tunnel opened, by the 1950s the highways connected through and by the 1980s skyscrapers began to dot the Jersey City skyline.

And that is the very (very!) abbreviated version of how Jersey City came to look like it does today. If it seems like I skipped hundreds or even millions of years at a time, it’s because I did. But hopefully, we all learned a little something.

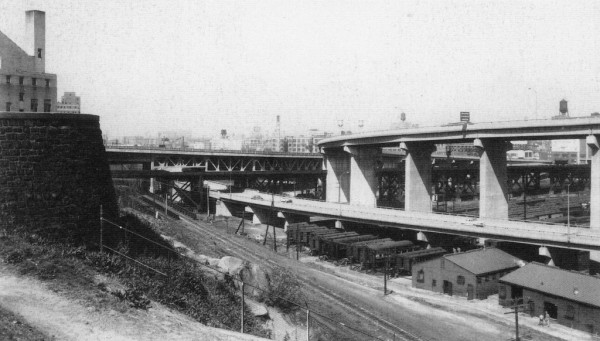

The Embankment Preservation Coalition has been working for 18 years to preserve, restore and rethink the Jersey City Embankment into a public use space. “We think that the embankment could be the jewel of a system,” said Luke. Their goal is to create something like the High Line in Manhattan, literally connecting Jersey City and figuratively connecting the past and present.

“One of the keys to success in Central Park was overpasses that separated pedestrians from motorized traffic, Luke said. “Jersey City doesn’t have a chance to create a Central Park… so our idea is to use the overpasses and underpasses of the embankment to tie Jersey City into a cohesive park.”

Find out more at www.embankment.org

You must be logged in to post a comment.